You are here

Changing State Perception of Nuclear Deterrence in Japan and South Korea

Summary

Japan and South Korea face the combined threat of an increasingly assertive China and a progressively more destabilising North Korea, not to mention a Russia which has resumed its role as a Pacific power. The US has enhanced its engagement with its East Asian partners in nuclear planning and consultation mechanisms. The prospects of indigenous nuclear weapons acquisition by Japan and South Korea, though, cannot be ruled out.

Introduction

In 2021, after Prime Minister Fumio Kishida came to office, Setsuko Thurlow, an atomic bomb survivor and well-known anti-nuclear weapons activist, urged him to sign the newly-negotiated Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW).1 She blamed the Japanese government for seeking continued protection from the very weapons that had been twice used on its soil by the very power that now guaranteed Japan’s security. She urged Prime Minister Kishida to sign the treaty and lead the campaign against nuclear weapons.

Japan however did not sign the TPNW and the nuclear umbrella of the United States remains intact. The nuclear programme of North Korea continues to churn, with little to no oversight by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). Russia, the world’s largest nuclear-armed state, continues to threaten the deployment of tactical weapons against Ukraine. China modernises its arsenal and refuses to participate in arms control talks until the US and Russia reduce their arsenals first.2

Kishida’s hesitation to sign the TPNW and commit to a non-nuclear stance reflects the threat perception held by East Asian democracies such as Japan and South Korea, as they face the combined threat of an increasingly assertive China and a progressively more destabilising North Korea, not to mention a Russia which has resumed its role as a Pacific power.

Evolving Nuclear Policy

Historically, Japan and South Korea were early adopters of norms against nuclear proliferation. Japan is a signatory to all major international treaties relating to nuclear weapons (with the exception of the TPNW), as is South Korea. However, in the immediate post-war period, both had very divergent views on nuclearisation. Japan aligned itself closely to a staunchly negative stance towards nuclear weapons, while South Korea attempted to actually pursue its own domestic nuclear weapon, even as both were protected by the extended nuclear deterrence umbrella of the US.

After 1945, as Japan slowly recovered from the war, its new constitution forbade it from possessing and maintaining any war-making capacity other than the bare minimum required for national defence. The US–Japan Mutual Security Treaty (called the Nichibei Anpo in short in Japanese), guaranteed the security of Japan by posting on Japanese soil a substantial number of forces who would, it was assumed, provide the offensive edge in the event of a conflict with the emerging Communist bloc.

Nuclear weapons were part of the bargain, though there was significant hesitation on the part of the Japanese to reveal the existence of nuclear-armed forces in Japan. This instinct was further confirmed in 1954, after the Daigo Fukuryu Maru (Lucky Dragon No. 5) incident, when there was a huge outcry in Japan against the US and Russia’s ongoing nuclear weapons tests. This led then Prime Minister Eisaku Sato to declare the cornerstone of Japan’s stance on nuclear weapons: the Three Non-Nuclear Principles. Under these, Japan would not allow possession, production or storage of nuclear weapons (by the US) on its soil.

Since then, despite the constant transit of US nuclear-armed submarines across Japanese waters, as well as the presence of the nuclear-powered US Seventh Fleet in Yokosuka Naval Base, Japan continued to maintain that its territory would remain free of nuclear weapons. It was partially these assurances which enabled it to become the only NPT non-nuclear signatory to possess the complete fuel cycle facilities necessary to reprocess uranium control rods from civil reactors into the high-yield variety capable of producing nuclear weapons.

South Korea had a different trajectory, one which led it to attempt to produce its own nuclear weapon in the 1970s. After independence from Japan, the Koreans were immediately embroiled in the Cold War due to the presence of Soviet and US troops along the 38th parallel bisecting the country. The Soviet-supported state, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), then invaded the weaker and less developed south, which under US control had become the Republic of Korea (ROK) in 1950, leading to the Korean War. This three-year conflict, which ended with the division of the country in 1953, resulted in the new ROK finding itself adjoining a Communist dictatorship that was perpetually attempting to destabilise it. Therefore, the military junta in power at the time under President Park Chung Hee decided that despite US security guarantees, the presence of US troops on Korean soil, and the extended deterrence provided by the nuclear umbrella, the ROK needed to have its own weapon3 .

In 1970, US President Richard Nixon’s declaration that the US would withdraw its troops from the Korean peninsula caused the South Koreans to set up the Weapons Exploration Committee4 , which explored ways of obtaining, processing and manufacturing enough high-yield plutonium to make weapons. The fall of South Vietnam in 1975 further heightened Korean anxiety, and hastened the development project. However, by 1975, the US, which had caught wind of the secret programme, pressured France to refuse to supply the necessary equipment, and the programme was shut down, though sporadic efforts continued till 19795 . By 1975, the ROK had signed the NPT, and placed its nuclear facilities under the IAEA inspection mechanism.

In 1991, President Roh Tae-Woo emulated Japan’s example and issued the Five Non-Nuclear Principles: the ROK would not manufacture, possess, store, deploy or use nuclear weapons.6 At the same time, the US removal of tactical nuclear weapons from the South led to gradual public support for a nuclear deterrent of its own culminating in the present majority support for hosting nuclear weapons on its soil.

Altered Threat Perception

North Korea’s rapid nuclearisation, and the rise of China to great power status have altered these countries’ threat perception. It was already well-known that North Korea possessed the wherewithal to manufacture nuclear weapons. In the 1970s and 1980s, Abdul Qadeer Khan started a network that explicitly (with the connivance of the Pakistani government) marketed nuclear fuel processing equipment and expertise that could only have been used in a nuclear weapons programme to North Korea.7 North Korea’s march to nuclearisation continued, and in 2006 it tested its first nuclear weapon. Despite United Nations sanctions, the North continued to develop its nuclear capability further, leading to the persistent missile tests that have become such a common sight today.

The initial response to North Korea’s tests were to conduct dialogue. The Six-party Talks8 , comprising the US, Japan, South Korea, North Korea, China and Russia, were intended to convince the North to give up its weapons in exchange for food aid, security guarantees and international recognition. However, the North Korean regime’s insistence on US forces being withdrawn from East Asia entirely, and its refusal to subject its nuclear facilities to IAEA inspection, doomed the talks to failure. Since then, North Korea has made increasingly belligerent threats of annihilation towards South Korea followed by repeated missile tests as well as further nuclear tests in 2009, 2013, 2016 (twice) and 2017.

A far more concerning threat, however, comes from China. After developing a nuclear weapon in 1964, China quickly developed thermonuclear weapons with the assistance of the Soviet Union, and in 1967 conducted its first test of that more dangerous weapon. Since then, it has maintained a strategic arsenal of more than 400 weapons. While China has signed the NPT as a nuclear weapon state, it has not signed the CTBT. China maintains a No First Use (NFU) policy, though statements by Foreign Ministry officials in recent times have indicated that NFU may be waived against certain opponents, such as India and Japan. Another concern altering threat perceptions is the fact that an aggressive China under President Xi Jinping has recently declared significant expansion of its nuclear assets, after refusing to participate in US–Russia talks on reducing the nuclear weapon stockpiles held by both countries.9

Japan and the ROK have responded cautiously to the security threats and provocations emanating from North Korean missiles tests and Chinese excesses. The barrage of missile tests last year by North Korea, continuing well through this year, have necessitated fundamental realignment in the traditional security structures the ROK and Japan have long relied on. The strategic documents released by Japan and the ROK in December 2022 and June 2023 respectively have amply reflected these realignments in light of acute provocations from the North as well as the systemic challenge posed by China.

Japan’s Response to Contemporary Security Challenges

Japan faces several regional and extra-regional security threats as reflected in the National Security Strategy (NSS) document. Chinese military activities in the Indo-Pacific region, both normatively and empirically, have “become a matter of serious concern for Japan and the international community.”10 With the ambition of “the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation”, China has increased its defense expenditure and has embarked on enhancing and modernising its nuclear and missile capabilities.

China has intensified unilateral activities in East and South China Sea as well as Sea of Japan altering the status quo in and around Senkaku Islands in the Sea of Japan. The issue of Taiwan also inextricably impacts the security dynamics of Japan. Evidently, a missile entered Japanese exclusive economic zone (EEZ) when a missile launch demonstration was conducted by China during Taiwan Strait crisis last year. Hence, China presents a long term, credible and enduring security threat.

On the other hand, North Korea presents an immediate security threat in terms of missile and nuclear provocations. There have been instances of cruise and ballistic missile tests conducted by North Korea including some of the missiles being launched over Japanese territory or falling within the EEZ of Japan setting off evacuation alarms across Japan. In yet another provocative steps to enhance its offensive military capabilities, North Korea made a failed attempt to launch first military surveillance satellite in June this year. Earlier in March 2023, before the ‘Freedom Shield’ joint exercise between South Korea and the US, North Korea warned in a statement that if the US took military action against the North’s strategic weapons test, it would be seen as ‘declaration of war’. Further, Kim Yo Jong, the sister of the North Korean leader, stated that “the Pacific Ocean does not belong to the dominium of the US or Japan.”11

The taboo of not threatening the use of a nuclear weapon appears to be diluting, which will have an inevitable impact on East Asian security dynamics. The threat of the use of nuclear weapons has continuously been issued in the ongoing Russia–Ukraine war. The importance that the Sea of Okhotsk plays in Russian strategic nuclear forces doctrine further multiplies their activities in Northern Japan. Joint naval drills and joint flight of strategic bombers with China appears to be yet another challenge, further amplifying the insecurity among the regional states.

In order to address these challenges, Japan has prioritised the US–Japan alliance as the core of their strategy. Further, Japan’s recently unveiled National Security Strategy and National Defense Strategy provide for reinforced capabilities including counterstrike and reconsideration of US-conceived integrated deterrence. Dramatic advancement in missile-related technologies including hypersonic weapons have rendered Japanese ballistic missile defences insufficient. It is for this reason that the NSS 2022 proposes adoption of counterstrike capabilities in effective coordination with missile defense systems. In what the document calls ‘flexible deterrence option’, it clarifies that first strike is impermissible. To advance these objectives, Japan is slated to increase its defence budget to 2 per cent of GDP by 2027.

The challenge for Japan can be summarised in 2 Ds—deterrence and disarmament. Under Prime Minister Kishida, who hails from Hiroshima, the government’s solemn commitment to disarmament is quite conspicuous. His government’s aggressive approach towards disarmament is shaping both governmental and non-governmental discourses. On one hand, Kishida spearheaded the establishment of the 15-member International Group of Eminent Persons for a world without nuclear weapons.12 In February 2023, the group convened their second meeting which recommended three main action points—reinforcing and expanding norms; concrete measures on nuclear risk reduction; and revitalising the NPT’s review process.13

Kishida also took a group of most industrialised G7 members (including Ukrainian President Volodmyr Zelenskyy) to Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park as a part of 2023 G7 Summit schedule. To set the discourse against the use of threat of nuclear weapons, as a part of G7 outcome documents, ‘G7 Leaders’ Hiroshima Vision on Nuclear Disarmament’ was also released.14

At the same time, Japan’s reliance on the United States’ extended nuclear deterrence presents a dichotomous situation wherein the US nuclear umbrella cannot be diluted due to its regional security implications, while the discourse around effectuation of disarmament must also be continued. Amidst the advancing nuclear and ballistic missile tests, including missiles launched by Beijing and Pyongyang last year in and over Japanese territory, Washington’s deterrence commitments have become more important than ever before for Tokyo.

South Korean Response to Contemporary Security Challenges

The security threat from Pyongyang is more acute in Seoul. Traditionally, under the US security umbrella, South Korea has increasingly found the alliance architecture insufficient to deter the North’s provocations. Since last year, North Korea has conducted over 120 cruise and ballistic missile tests as a response to the trans-Pacific alliance between the US and its East Asian partners. In past years, the North Korean threat of deployment of tactical nuclear weapons and preemptive nuclear strikes has further strengthened the multi-dimensional US-ROK security alliance. Besides the threat of North Korean Weapons of Mass Destruction, convergence of strategic interest between China and Russia, as also the unfolding great power competition between the US and China, present eminent challenges for South Korean security interests.

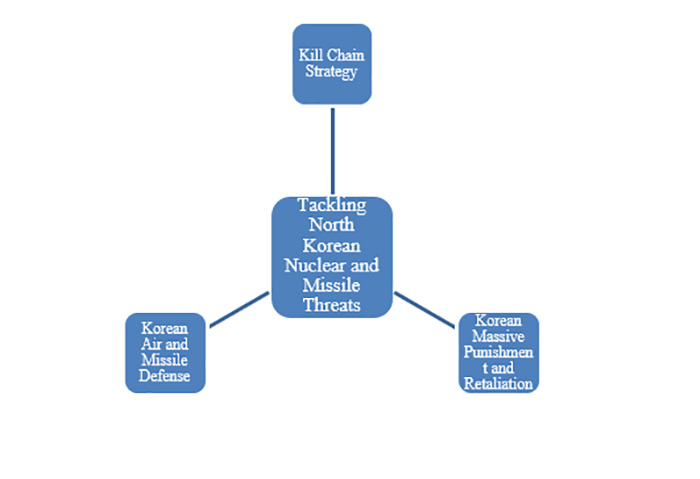

Acknowledging the emerging threats—including the adverse impact of the Russia–Ukraine War, the Yoon Suk Yeol Administration came up with a new National Security Strategy (NSS) in June 2023. The document underlines the solidification of extended nuclear deterrence in the ‘Washington Declaration’15 which entailed the establishment of a Nuclear Consultation Group, deployment of US strategic assets and commitment to extended nuclear deterrence. It further details a South Korean ‘three axis system’ to tackle North Korean nuclear and missile threats based on three stages of confrontation—preemption, defense strategies and retaliatory strategy (Figure 1).

These are Kill Chain strategy, Korean Air and Missile Defense (KAMD), and Korean Massive Punishment and Retaliation (KMPR) respectively. Kill Chain strategy aims to preemptively destroy North Korean nuclear and missile assets in case of clear indication of their intention to use nuclear weapons. Hence, it relies upon sophisticated surveillance and reconnaissance assets, along with precision strike capabilities. KAMD is a complex, multi-layered defence system that is designed to detect and intercept various types of missiles. KMPR aims at punitive massive retaliation with overwhelming force in order to deter North Korea and convey that the repercussion of its first strike would be so overwhelming that any perceived benefits from a first nuclear strike would be outweighed.

Conclusion

The presence of the US extended nuclear deterrence to Japan and South Korea has ensured stability in the East Asian region for decades. However, deterrence has increasingly been diluted ever since the acquisition of nuclear weapons by North Korea in 2006. While domestic debates on nuclear weapons gained urgency given Chinese and North Korean provocations, South Korean President in January 202317 called for the deployment of US nuclear weapons or development of an indigenous nuclear weapon capability. The US has responded by enhancing engagement and integration of its East Asian partners in nuclear planning and consultation mechanisms. With increasing North Korean nuclear and missile threats, and Chinese nuclear force modernisation, the prospects of indigenous nuclear weapons acquisition by Japan and South Korea cannot be ruled out.

Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

- 1. Mainichi Shimbun, “A-bomb survivor Setsuko Thurlow hopes Japan's new PM can lead nuclear disarmament debate”, The Mainichi, 6 October 2021.

- 2. Gabriel Dominguez, “G7 adopts Kishida’s vision for a nuke-free world, but disarmament likely elusive”, The Japan Times, 20 May 2023.

- 3. “South Korea Special Weapons”, GlobalSecurity.org.

- 4. Ibid.

- 5. Ibid.

- 6. Ibid.

- 7. Molly MacCalman, “A.Q. Khan Nuclear Smuggling Network”, Journal of Strategic Security, Vol. 9, No. 1, p. 111.

- 8. Xiaodon Liang, “The Six-Party Talks at a Glance”, Arms Control Association, January 2022.

- 9. “China”, Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation.

- 10. “Japan’s National Security Strategy 2022”, Government of Japan, p. 9.

- 11. “Kim Jong Un’s sister warns: ‘Pacific Ocean not dominium of the US or Japan’”, The Indian Express, 7 March 2023.

- 12. “Members of the International Group of Eminent Persons for a World without Nuclear Weapons”, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, 2 December 2022.

- 13. Manpreet Sethi, “Lending a helping hand to the first NPT PrepCom for the Eleventh Review Conference”, Asia-Pacific Leadership Network, 24 July 2023.

- 14. “G7 Leader’s Hiroshima Vision on Nuclear Disarmament”, 19 May 2023.

- 15. “Washington Declaration”, The White House, 26 April 2023.

- 16. Compiled by the authors from “The Yoon Suk Yeol Administration’s National Security Strategy: Global Pivotal State for Freedom, Peace and Prosperity”, Office of the President Republic of Korea, June 2023.

- 17. Abhishek Verma, “The Washington Declaration and US-South Korea Relations”, Commentary, Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (MP-IDSA), 10 May 2023.